NOTE: I want to thank everyone for their concern following the violent event that took place today at Fort Lauderdale Airport. I am okay. Thankfully, I was some distance away in Miami Beach reading National Park Service Records on the Art Deco District.

“The industry is tourism and the fuel is the sunshine,” was the partial description of Miami Beach provided in its application for federal protection.

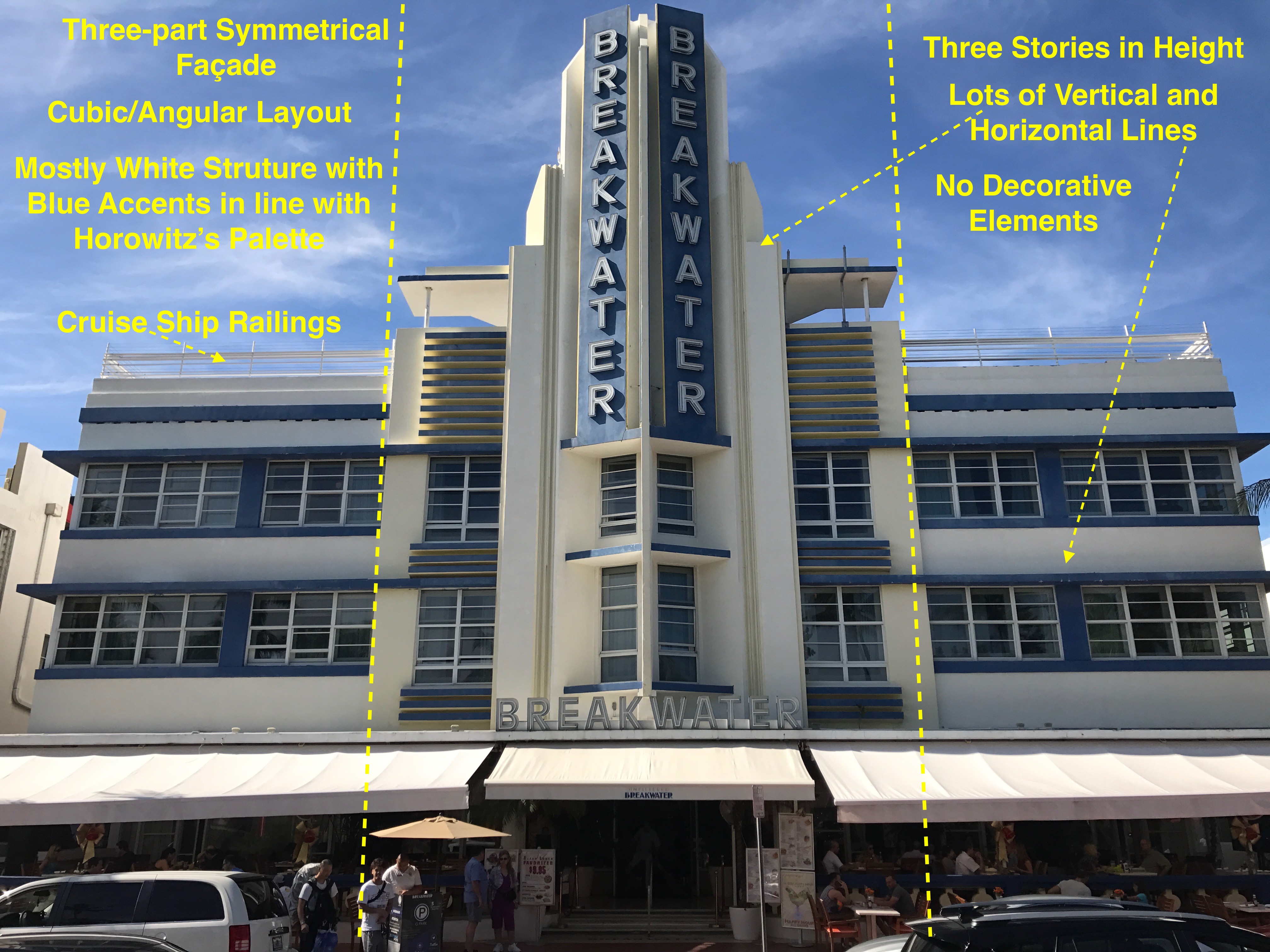

The Breakwater

However, Miami Beach had not always been a beach destination. The island’s first use was as a coconut farm in the late nineteenth century, which quickly failed.

An early investor, John Collins, deviated from coconuts. He managed to successfully grow Avocado and that allowed him to slowly buyout the surrounding plot owners in the southern part of the Island, known as South Beach.

The main thoroughfare, Collins Avenue, is named after him.

Collins wanted a better way to get his produce over to the mainland. He came up with a plan leading to the construction of the longest wooden bridge in the world in the 1912.

But, he ran out of money before it could be finished.

Recognizing South Beach’s potential for vacationers, American entrepreneur Carl Fisher (architect of Indianapolis Motor Speedway), financed the completion of the bridge.

Collins and Fisher together created a beach destination for the very wealthy or as we might say today the “top one percent.”

In 1926, the “Great Miami” hurricane brought devastation, razing almost all of Miami Beach.

Undeterred by this event, South Beach was rebuilt.

At this point, a new type of design in architecture, first seen at the 1925 World’s Fair held in Paris, emerged: Art Deco.

World Fair Poster for Paris 1925

This style was a departure from the humble construction World War I prescribed.

People wanted to move past the war. This desire inspired a futuristic, cubic looking construction.

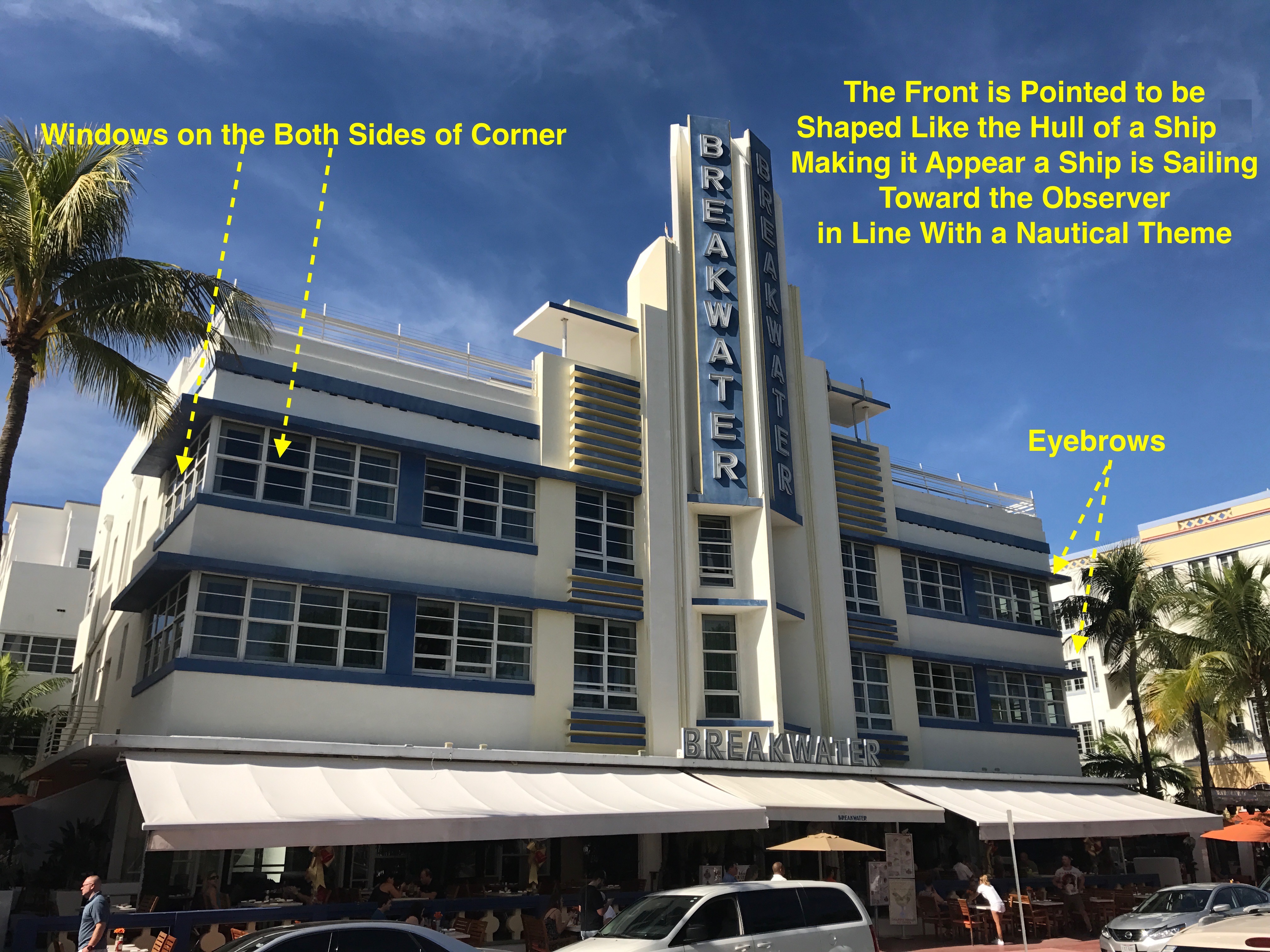

In Miami, there is a whimsical feel through a nautical theme in many buildings, evoking a fun beach scene.

Porthole windows and cruise ship railings are a common feature. Some hotels even marketed themselves as a cheaper alternative to the big ships, while still maintaining a sense of sailing.

The nautical theme later gave way to the use of large windows and balconies in what became characterized as “Miami Modern (MiMo)” Art Deco.

Typical construction is a symmetric, three-part façade. Some describe the construction as angular, though designers occasionaly incorporated cylindrical corners. There are many vertical and horizontal lines that create the illusion of “movement,” an acknowledgment to the modernization of transportation taking place during this era.

Several common elements help define the Art Deco found in South Beach: eyebrows, light colors (often white or beige), windows on each side of the corner, and terrazzo floors.

The eyebrows are found above the windows. Beyond just being decorative, they cast a shadow on the window when the sun is directly shining. They help prevent the temperature to increase, particularly important before the availability of air conditioning.

Most of the buildings were originally white, which helped reflect the sun and thus served as yet another strategy to fight the hot weather conditions in the region.

Also, placing windows on both sides of the corner helped foster a cross draft inside, creating a cooling effect.

The majority of the buildings are only three stories high because a local ordinance required buildings exceeding this height to install elevators, an expensive luxury at the time.

Example of Miami Modern (MiMo)

Inside, floors are constructed of a marble and concrete mix that is polished, called Terrazzo. This also helped mitigate hot temperatures and was easy to maintain.

The Terrazzo floor at the National

Distinctively, all the sidewalks are painted red, to make people feel as though they are walking on the Hollywood Red Carpet like the movie stars.

Finally, there are few decorative elements on the façades, a response to the Great Depression, which began in 1929, four years into Art Deco’s heyday.

The Great Depression forced South Beach to rebrand.

One story goes that the shrewd Fisher decided to now tailor and promote South Beach toward the middle class despite unemployment rates hitting about 25% during the Great Depression.

The optimistic Fisher felt this meant there was a market share of 75% of employed workers to attract. Fisher further recognized that Union Labor had been successfully negotiating the benefit of paid vacation through collective bargaining. He reasoned that these workers would be looking for a place to vacation irrespective of any depression.

This approach had success until the United States entered World War II, when everyone focused on the war effort.

The Army, needing beach training grounds with good weather to train in, took over the South Beach area. Over 500,000 cadets passed through South Beach in support of the War.

After the war, South Beach went into decline despite visitors flocking back to Miami Beach in the post-war boom, particularly veterans who fondly remembered their training grounds.

Newer, contemporary construction had taken place in the middle portion of the Island, Mid Beach, which syphoned away tourism from South Beach.

The new construction in Mid Beach had one significant innovation over the buildings in South Beach: Air Conditioning.

By the 1960’s, South Beach was nicknamed “The Living Room of the Elderly,” reflecting the demographics that could not afford the more expensive Mid Beach area.

As the available real estate in Mid Beach began to diminish in the 1970’s, developers started spreading into South Beach, bringing “capricious destruction” to make way for construction that no longer was inspired by Art Deco.

This un-moderated redevelopment of South Beach drew the attention of Barbara Capitman. She was a journalist who became a dedicated preservationist.

Realizing South Beach was an exceptional example of Art Deco and dismayed by its probable loss, she committed herself to the area’s conservation.

She cataloged more than 800 instances of Art deco inspired design throughout South Beach by photographing each one and documenting its history.

Her research revealed that an “approximately 125 square block area contained the largest concentration of the 1920’s and 1930’s era” Art Deco buildings in the United States.

“This uniformity of scale and architectural style has remained largely intact despite the pressures of wholesale development in areas adjacent to the District,” she wrote in the nomination application for South Beach to be placed on the National Register of Historic Places by the National Park Service.

This was “remarkable, particularly given the comprehensive nature of the District: it includes residences (both single-family and multiple-unit buildings) as well as commercial buildings, theaters, governmental, educational and recreational facilities and the very important seasonal hotel,” the application continued.

Her endeavor was successful and was the first step in ensuring this unique national treasure would be adequately protected and preserved.

It was the first twentieth century historic district placed on the register.

Tribute to Capitman

Although the area gained federal recognition that provided some support, local ordinances still needed to be lobbied for to ensure safeguarding of the Art Deco District.

Further challenges were brought on by the fact tourist infrastructure for visitors to enjoy was very limited. There was not a single restaurant on Ocean Drive, today’s main drag and many storefronts in the surrounding area were vacant.

Barbara Capitman’s son, Andrew and his wife Margaret were among the first to take a chance by investing in seven properties. Together, they fully restored them as hotels and restaurants, which played a key role in the revitalization of the Art Deco District. Their success inspired others to follow suit.

Additionally, an industrial designer by the name of Leonard Horowitz found his way to his mother in South Beach after being disowned by his father upon learning Horowitz’s sexual orientation.

Horowitz, intrigued by the preservation efforts, reasoned that the white color of the buildings, originally preferred because it reflected back the heat of the sun, took away from the grandeur of Art Deco.

He introduced a palette of pastel colors based on the colors one finds at the beach. This novel idea led to national recognition, increasing visitors. Soon after this, many buildings throughout the neighborhood adopted color.

Some even say, “Color saved the Art Deco District.”

The Palette Horowitz Developed

“No matter the crazy people or their fancy cars, I appreciate the sense of being frozen in time by the unique Art Deco buildings. Their consistency is a reminder I am home,” a hostel worker told me when discussing her love of the city.

Locals and tourists alike have Barbara Capitman to thank for her vision and perseverance. The timeless ambiance that remains here inspires millions of guests to visit this architectural gem of Florida each year.

Special thanks to Marty from Art Deco Walks and Martin from the Miami Design Preservation League for their insightful tours. Additional thanks to the National Park Service archives, which had the original nomination paperwork available for download.

// Oliver – Day 6 – Miami